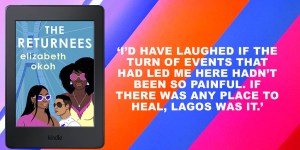

Free Extract: The Returnees by Elizabeth Okoh

An unforgettable tale of female friendship, love and mistaken identities set in modern Nigeria, from an exciting new voice in women’s fiction.

After a bad break up, 25-year-old Osayuki Idahosa leaves behind everything she holds dear in London to return to Lagos, Nigeria: a country she hasn’t set foot in for many years. Drawn by the transformations happening in the fashion industry in the city, she accepts a job at House of Martha as their Head of PR. While waiting at Milan airport for her connecting flight to Lagos, she meets Cynthia Okoye and Kian Bajo, a wanna-be Afrobeat star. After the plane lands at the Lagos airport, they all go their separate ways but their lives will intertwine again and change the course of Osayuki’s life forever.

THE NAMING

Present Day

I

Osayuki

The sweet smell of Fairy Dust wafts into my nostrils from where it burns on the marble stool I’ve placed by my white stone bathtub. The scented candle had been hand delivered only five days before by Cynthia, one of my closest friends, who had picked it up from a boutique shop in Covent Garden on her way from London. That candle shop had been one of my guilty pleasures. Back in the day, I could easily have spent hours in there, watching as the small batches of handmade candles were set into jars and then left to cool at the far end of the shop.

When I’d finally leave, I’d be on a sweet-smelling high with a new stock of Fairy Dust and sometimes Wild Berries in my bag; but that was years ago. Now living in a beautiful house in Lagos, tastefully decorated thanks to Pinterest boards and 3 a.m. calls to suppliers in China, I am still the same carefree and adventurous girl, but in a different city – one that, equally, does not sleep.

The bath water is beginning to feel lukewarm, so I pick up my sponge and start scrubbing my neck, then my arms and enlarged breasts, which now hold milk and are a size that I’ve only come to know over the last couple of months. I do ten reps of the Kegel exercise and massage my thigh, just below my moon tattoo, and then scrub my belly. It is no longer as firm as it once was. Giving birth does that to you. I have expected these changes, but living through them is still a wonder on the days I feel like my old self and can’t believe that I am now a mother.

Through the small slit between the bathroom door and its lock, I hear the voices in the other room. Someone has come in and I think I hear Cynthia saying the guests have started to arrive. This information doesn’t make me rush; I know Mum will knock on the door when it’s time. I lean back again and rest my head on the edge of the bathtub.

Twenty minutes later, I walk out of the bathroom to find that my red-and-silver-coloured asoke is laid carefully on the bed. I sniggered when mum told me the market seller had assured her that the woven fabric had been made by the best hand-loomers in Ibadan. ‘Ahn ahn . . .’ Mama Fola had drawled, neither confirming nor disputing the claim, although her coy smile had attested to the latter.

I get ready in the bedroom that I had prepared for my mum and step-dad, Bob. He is already downstairs with our guests while Mum and some female relatives are helping to prepare me for my baby’s naming ceremony. I pick up my iro – a Yoruba word for a large piece of fabric worn as a wrap-around skirt – and look it over. It is beautiful. Mum made a good choice at the market weeks ago when I was still heavily pregnant and unable to leave the house. It is crazy that only eight days ago, my baby boy, Nimi, was still inside me. I didn’t expect my last trimester to have been so testing, but now my son is here, I am happy to announce his arrival to the world in the way required by my husband Fola’s Yoruba tradition.

I wonder what Fola is doing. I guess that he is most likely ready and waiting for me, but I am in no hurry. We still have to get Nimi dressed. I put on my iro and buba – a blouse – and then sit on the bed while a friend of Mama Fola ties my gele on my head. Mum is dressing Nimi, and when he stirs and begins to cry, I know he needs another feed. We stop the head tying and Nimi is passed over to me. He latches on with toothless gums and I flinch. I am still getting used to being a new mum and it still hurts whenever he clings to my breast. Eight days in and I am still figuring out what being a mother entails. No one told me that it would hurt for this long. But I love my son and would do anything for him. This was once a cliché to me, but now I fully understand it.

An hour later we are all dressed and ready to start the cere- mony. Fola joins us outside the room. I pass Nimi to him and we all make our way downstairs to the waiting party. The house, a three-bedroom duplex, is in a coveted area in Victoria Island, only a fifteen-minute drive from my Aunty Rosemary’s house. I fell in love with our place the first time we went for a viewing, despite the previous owners’ questionable taste in decor. It still pains me to think of all the garish furnishings adorning the inter- iors of Lagos’ most lavish houses. ‘Money can never buy class!’ said my friend Wendy when I aired my frustration. We signed the papers and put down a deposit for the house a few days later, and thus began my task of making it fit to move into with my new family. I had initially worked with my own ideas and then completed the makeover with an interior designer, and the house that Fola and I would call our first home was ready to be inhabited just in time for our baby’s arrival.

Our families quieten down as Fola and I walk into the brightly lit living room, decked with gold accents and large framed illus- trations. When we were decorating, I had ordered an oval gold-framed mirror and asked that it be hung on the wall just before the marble staircase. When I instructed that another be put in the living room, Fola had protested. He said we ‘weren’t vain people’. So instead, we hung pictures of us in our traditional wedding attire and at our reception, both of us smiling like we had won the lottery. Perhaps we had.

Our new chandelier with teardrop diamonds is glittering above our families and guests. Just behind my parents, I can see my friends and my Aunty Rosemary, along with her husband Osi and my cousins.There are some other relatives I don’t know too well – I smile at them all as we walk in. Fola’s family and friends are there too. We beam with pride and take our seats at the head of the gathering, with our parents on either side of us.

Mama Fola’s pastor is already at the front of the room waiting to proceed with the naming ceremony. It is a tradition that has to take place on the eighth day after the birth of the child. On the table next to the pastor are bowls containing substances the Yoruba people believe are essential to a child’s start in life – honey, salt, sugar, alligator pepper, palm oil, kola nut, bitter kola and water, all of them a representation of goodwill and prosperity. Fola passes Nimi to the pastor and the ceremony begins. A prayer is said, followed by the recitation of a hymn from an Anglican hymn book.

Nigerians say that when your palms are itchy, money or good fortune is coming your way. But itchy palms have always spelled trouble for me, and I wonder why it has to be at this moment when I am carrying Nimi in my arms that my left palm decides to itch its way to madness. I badly want to scratch the damn thing, but I can’t let go of my son, so I try my best to ignore it. I smile as the salt is rubbed on the tip of his tongue and he contorts his face. That there is the beautiful thing I love about the Yoruba culture. But I have also learned that tradition is something that can hold someone captive; that can turn them stone cold to any concept of reasoning and make them refuse to grow or think for themselves. I once heard a lady on a yellow danfo bus swear that culture and religion stunt the growth of Nigerians more than anything else, after a preacher stopped by to deliver a sermon in the fifteen minutes it took for the bus to load full of passengers. ‘Na inside this hot sun where person dey find peace, wey him kon dey shout on top of our head? Abeg, make we hear word!’ she hissed. I couldn’t have agreed more. So when I do fawn at the beauty of culture, I do so with finger-measured adulation.

The Yorubas believe that just as honey is sweet, so will be the life of the child, and just as salt adds flavour to food, so will the child’s life be full of substance and happiness. The sugar also represents a sweet life, and just like the plentiful seeds in an alligator pepper, the child’s lineage will multiply. Palm oil is to signify a smooth and easy life, while the kola nut is to repel evil. The bitter kola is for a very long life and, finally, water is present so that the child is never thirsty in life and so that no enemy will slow its growth. I taste each and rub them on my poor baby’s mouth, this small creature of mine who is still breathing new, unrecognisable air, another life in a terrible yet wondrous world. I hope the world won’t be cruel to him.

I have already decided that my Nimi will be a feminist. Fola nodded in agreement, knowing better than to argue with me. I want him to play with dolls just as much as he does with cars. I want him not just to enjoy egusi soup but to know how to cook it too. I want him to know what it is to love a woman whole- heartedly, so that her submission is never a conversation at the dining table. As well as knowing how to repair a car, he’ll know how to do his own laundry. By God, he’ll learn to do it all, and where I fail, Fola will come to the rescue, teaching him what I cannot.The world desperately needs more feminists and my Nimi is going to be one.

II

Osayuki

I am upstairs in my bedroom taking a much-needed break from the celebration downstairs. I have fed Nimi again and he is peacefully asleep in his grandmother’s arms. I can already tell that Mama Fola will spoil him. She had happily taken him from me when I said I was coming up to the room. ‘Go and rest a bit my dear,’ she had nodded in understanding. The formal part of the ceremony is over and everyone is helping themselves to the food we prepared for the big feast. But before this, the pastor called on both grandparents to hold Nimi, to give him a name and pray for him by declaring great things into his life. Later on, other relatives were also given a chance to give him a name if they wanted to, but they were first required to put money into a bowl. At the end of the ceremony, Nimi came away with five names. But Fola and I know that there are only three that will make it to his birth certificate. The one we have given him – Oluwalonimi, a Yoruba name meaning ‘God owns me’, due to the circumstances of his conception; Ife ̇le ̇wa, another Yoruba name meaning ‘beautiful love’, given by Fola’s mother; and Osaze, given by my mother, meaning ‘chosen by God’ in our Edo language. Our little boy will be known to the world as Oluwalonimi Ife ̇le ̇wa Osaze Morgan, beautiful names rooted in love and God’s grace.

I take off my heels and relax into the flower-patterned chaise longue adjacent to our king-sized bed. I stretch out my legs and turn on the TV to distract me from the headache I am beginning to feel, thanks to the tightness of the gele on my head. I look for the knots. While I loosen them, I watch the news on the BBC. They’re talking about a young man who died a month ago while on a trip to Nigeria. The reporter says that he was a third-generation British-Nigerian man, and had been in his mother- land for over a year before his untimely death. Not today, oh not today. I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe.

I am shocked to the core and, all of a sudden, I feel numb. I stare at the TV in silence, my lips trembling, watching flashing images transition from a solemn crowd in London gathered at a graveside, to a bustling junction in Lagos, overflowing with market sellers. I try to process what I am hearing. I knew that the day would come when I’d have to make a decision. But why today? The day of my baby’s naming ceremony. Is it a sign? I realise I am covered in goosebumps and the once humid room now feels cold. I grab my throw and wrap myself in its faux fur. Without warning, tears begin to race down my cheeks.

Moments later, I hear the loud clickety sounds of stilettos on the marble floor outside, coming towards my room, and I grab a pocket tissue and quickly dab my face, making sure I don’t ruin the makeup Cynthia had perfectly applied this morning. I fluff my buba, pat down my iro and compose myself. No one must know what is unravelling in my head. The news on the TV continues to recount the events that led to the young man’s death by the roadside. I bend over and tie the straps of my heels back up. I look up to find Cynthia leaning against the door frame, staring at me with arms akimbo, accentuating her hourglass figure even further.

‘Yuki what are you doing here? Hiding away while the rest of us attend to the guests huh?’ she drawls. ‘You’re lucky today is your day, you know I dislike babysitting adults at parties, especially these aunties we all know are here just for the food! I don’t know what it is with Nigerians and party jollof,’ she continues, exaggerating the last two words as they roll off her tongue.

She walks over and joins me on the chaise, nudging her big bum against mine, an order to scoot over.

‘Don’t tell me you’re already tired? You’ve only worn that head tie for like . . . an hour? Come on, give me a break!’ She goes on, relaxing into the chair and making herself comfortable.

‘So why are you sitting down then?’ I smirk.

‘Well if you can sit, so can I!’ she counters.

She picks up the remote and I attempt to collect it from her, but she is too fast. She sways it out of my reach and turns up the volume. I can tell that she is going to sit for a while.

‘Oh God, he looks familiar,’ she says.

‘Who?’ I ask, pretending not to understand.

‘Were you not just watching this? He looks familiar, but I don’t

remember where.’

‘I’m sure every good-looking guy looks familiar to you Cynthia.

Please, let’s join the others downstairs. Who’s with Nimi?’ I change the subject.

I get up, take the remote out of her grasp and turn off the TV, even though I know that she still won’t follow me immediately. With shaky legs, I walk towards the door, glad that my back is now to her, hiding the tremor in my lips and the tears welling up again in my eyes.

I pause. ‘Let’s go, I don’t want people wondering where the mother of the day is,’ I say, and walk out.

‘Go on, I’m right behind you,’ Cynthia says while still seated, one foot now crossed over the other.

I don’t bother urging her any further. I need the time it will take to walk from my room to the winding staircase and down into the living room to get myself together and be the proud, smiling mother that I was a few minutes ago. Even though my sanity is beginning to crumble, I have to put on a facade for the rest of the day until the last of the guests are seen out. Like a swan, I have to be regal and glide with charm, even though underneath I am swimming for dear life.

III

Cynthia

Finally alone, I turn the TV back on and take off the corset that is holding my tummy in. It had been amusing to watch Fola’s mother try to convince me to eat that mound of pounded yam. She had got quite upset when I had refused to, seeing as it had been dished out with my favourite soup.

I had followed Yuki upstairs, hoping to chat to her about my latest struggles with setting up my beauty academy back in London. The road to being self-employed is definitely not as linear as I had imagined when I first thought of the idea to create a brand to help women build their self-esteem through makeup. Yuki always knows how to put things into perspective, so I had hoped we’d get a chance to chat properly before I returned to England.

‘I’ll just close my eyes for five minutes,’ I think as I stretch my legs on the chaise longue. But just a few seconds later, I am brought out of my dreamland by the news reporter’s solemn voice. I sit up and watch with keen eyes. Something is amiss. I’m not sure what it is, but I know exactly who can explain it to me. I head back downstairs.

I’ve been watching Yuki for an hour now, and something is definitely up. She no longer has that spring in her step or that glow in her eyes. If anything, she looks on the brink of tears. It might not be visible to the undiscerning eye, but I know her well and I know that something is wrong. I look at Fola who is seated beside her and wonder if he too can tell.

‘Of course he can.’ I answer the daft question in my head and fan myself with a newspaper as the help runs out to turn on the generator again. For the second time this afternoon, the power has gone out. ‘Ah NEPA!’ comes the familiar lament. Nigeria’s National Electric Power Authority, long ago privatised and given a new name, has been providing such treats for years. But the disappointment is fresh every time, like a mother who suddenly realises that her son is now grown and no longer wants to be kissed in public.

Some hours later, when everyone has eaten their fill, I try to help Yuki cut the cake to serve to the guests, but she shoos me away. This isn’t unlike her. If there is one thing that I know about Yuki, it is that she loves to keep herself busy whenever she is stressed or on edge about something. She would rather move around, sing, dance, or do anything other than sit twiddling her fingers, or try to keep still while her body involuntarily fidgets. I look at her closely before I leave to help the other women in the kitchen bring out more drinks. The guests are clearly still enjoying being merry, and the quick wave of her hand gives just enough time to blink back tears. She isn’t fooling me.

The day carries on gallantly. Everyone is all smiles, especially the proud parents. That sweet smile of Yuki’s easily captures the hearts of most, but I can tell it is sometimes forced. Fola, on the other hand, beams with pride, as any new father would. It is a wonderful ceremony for a wonderful couple.

We eat, dance and share many stories that evening. I have never seen Fola’s mother as excited as she is today; she is known for her dramatics, but she has surpassed even herself. And Yuki’s family are no different. Her mother, who was up the whole previous night, helping her to tend to Nimi, is still on her feet seeing to everyone’s needs. She is clearly a doting mother. Although she was shocked to find out that Yuki was expecting a child after only being away from London for a year, she was still very supportive of her choice and new life. It has been a perfect ceremony, and knowing Yuki, it couldn’t have been better executed. However, I can’t shake off the feeling of foreboding.

I wait until most of the guests have left, and believe me, it is a long wait. It is no news that Nigerians love to party and at any given opportunity will turn a small ceremony into an all-night event. But thankfully, at about 9 p.m., the guests start to go home, and it is clear that there will be no partying into the wee hours of the morning. Mother and child both need their rest, after all.

After seeing Aunty Rosemary and her family to the door, I cast my bait.

‘Yu-ki,’ I drawl, as I usually do when I need a favour. I want to make her feel comfortable. ‘You must be knackered, let’s go upstairs for a bit.’

I can tell by the way she pauses that she would rather busy herself in the kitchen than go upstairs with me. But she must know I’m onto something – she’s caught me staring at her several times so far this evening.

‘Come on, you’ve been up since morning. Most of the guests are gone now, let’s take a break. Fola can see the rest of them out.’

‘Let’s take a break, or you need a break?’ she jokes.

I play along and give a fake laugh, but the walk up the winding stairs to the room is clearly awkward and I don’t know what I’m going to say when we get there. I just hope she opens up and tells me what is troubling her. When we get to the landing, I lead the way into the bedroom. As soon as she enters, I close the door – I want to make sure no one will walk in on us. Then, immediately, I pounce.

‘What’s going on? Come clean!’ I demand.

‘What do you mean?’ she asks shakily.

‘I know you well enough to know that something’s wrong.

What, did you think I wouldn’t notice?’ I say.

‘Cynthia, I’m tired, I thought we were coming up to rest?’ ‘Now you want to rest? Come on, it’s been quite obvious.

You’ve been acting weird since this afternoon. I mean, don’t get me wrong, you’ve been hiding it well, but I know something’s up. I’m surprised Fola hasn’t said anything to you yet – or has he?’ I continue, ignoring her evasion.

‘You’ve started with your exaggerations again. I’m fine, just a bit tired, that’s all.’ We both know that isn’t true.

‘If you won’t tell me, I’ll have to force it out of you one way or the other or should I ask Fola?’ I challenge.

‘Are you mad? Don’t get him involved in this!’

‘Oh really? So are you going to tell me what has upset you? Does it have to do with what was on the TV?’

As soon as I mention this, her demeanour changes. Faced with my stern look, she sits down on the bed and breaks into a flood of tears.

‘I don’t think I should tell you,’ she starts. ‘You don’t need to know . . .’

‘Clearly I do, and if you don’t tell me, I’ll find out one way or another before I leave for London. Osayuki, start talking!’ I haven’t used her full name in a long while.

Her next few words leave me in shock.With my head spinning, I reach for the bed. I sit next to her, head in hands and mouth ajar as I look on, incredulous. It’s an expression every Nigerian knows all too well.

‘How did this happen? When?’ The questions tumble out of my mouth.

It doesn’t make sense. None of it does. From the little that I can recall, she disliked Kian from the start. How has she found herself in this mess? I look at her for answers, and her eyes begin to well up again.

‘It happened so fast,’ she manages in between sobs.

‘I thought you had only been with Fola since you arrived?’ ‘I know what you must think of me. It only happened during our break!’

‘Ahh . . . the break that only lasted for like three weeks?’

‘It was a month, but that’s beside the point. I thought I was

never going to get back with him. He was dead to me, remember what happened?’ she says, trying to choke back fresh tears.

‘Hold on. You need to start from the beginning. How did it happen? You definitely didn’t like Kian at our first encounter,’ I reply.

‘No, I didn’t. But when we bumped into each other again at your leaving party, something was different about him, or maybe I was mad from the whole Fola situation. I don’t even know,’ she says, exasperated.

This is the first I have heard of her meeting Kian again. ‘Have you kept in contact with him all this time?’

‘No, I ignored all his calls and eventually he stopped calling. It was just that one night. And now it’s turned into an episode of Jeremy Kyle. Ah!’ she sighs.

‘So, he’s Nimi’s father?’ I ask, not wanting to believe the words as they stagger out of my mouth.

‘No. I mean, I don’t know!’

‘How can you not know? OK, start from the beginning.’

Did you enjoy the free extract? The Returnees is available to pre-order now!